By Clayton T. Baumann, PE, CCP, ASA | evcValuation and Christopher T. Rigo | evcValuation

Click HERE to download a PDF version of this article

Abstract

The development of wind farms in the U.S. has exploded over the past 20 years. Federal and state level incentives, state-mandated Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS), and property tax abatements are some of the factors that have helped fuel this significant growth. As the incentives and property tax abatements begin to expire, wind farm property owners are increasingly seeking the assistance of appraisers experienced in the power generation industry and knowledgeable in the intricacies of valuing a wind farm for ad valorem tax purposes. The following discussion provides history and background information and outlines key factors an appraiser should be intimately familiar with and thoroughly consider in the income approach to value when appraising a wind farm for ad valorem tax purposes.

Background and History

Wind turbines harness the kinetic energy of the wind, converting it to mechanical energy, which turns an electric generator to create electrical energy. Of the two different types of wind turbines—vertical axis turbines and horizontal axis turbines—horizontal axis turbines are the most commonly employed in the wind power generation industry. The typical components of a horizontal axis turbine consist of the blades, a drive train, and a tower.[1] The detailed components are illustrated in the figure below.

Source: https://www.energy.gov/eere/inside-wind-turbine

Humans have harnessed wind energy for thousands of years. Small wind turbines have long been used to pump water from wells, grind grain, and power sawmills. As early as the late 1800s, people began to use wind energy and generators in their homes. However, the 1930s’ expansion of transmission lines into rural areas made electricity more widely accessible, leading to a decrease in the number of wind turbines used to power homes. Oil price increases in the 1970s renewed the interest in wind power, fueling research and development of more advanced technologies. By the 1980s, wind farms began to dot the landscape across the U.S., including locations such as California, where thousands of turbines were installed.[2] In 2020, total installed wind capacity in the U.S. grew to 121,985 MW,[3] approximately 11% of the total U.S. generating capacity, up from just 0.2% in 1990.[4]

Development Incentives and Mandates

Since the 1980s, both the federal government and many state governments have used incentives to promote the development and use of renewable energy sources, including wind.[5] Federal tax credits, including the Renewable Electricity Production Tax Credit (PTC) and Business Energy Investment Tax Credit (ITC), have been made available to wind project developers. A qualifying wind farm facility can claim ITCs or PTCs, but not both.

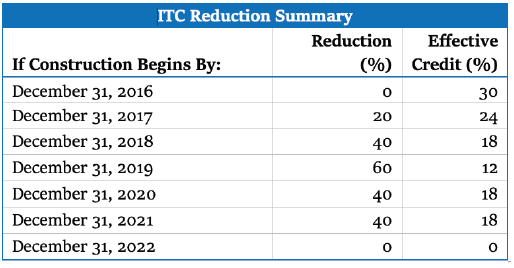

The ITC is a federal income tax credit, equal to 30% of the total qualified costs of a new wind farm project. Prior to 2019, the ITC was available to wind energy projects if construction commenced after December 31, 2016, and was reduced each year before eventually being phased out if construction did not commence prior to January 1, 2020. A 2019 year-end federal government spending bill extended the ITC expiration by one year.[6] The ITC incentive was further extended in 2020, through the Taxpayer Certainty and Disaster Tax Relief Act of 2020. This legislation extended the ITC incentive for an additional year for qualifying wind farm projects if the construction started prior to December 31, 2021.[7] No incentive is available for projects that begin construction in 2022. The ITC phase-out schedule is outlined in the following table.

The PTC is a federal income tax credit that a new wind farm project, or an existing project that has been repowered, can utilize when generating energy and selling the energy to an unrelated party. PTCs are available for the 10 years following the date the new wind farm project is placed into service. The PTC value is inflated annually, per Internal Revenue Service (IRS) publications, and for 2021 is equal to 2.5 cents per kilowatt hour of electricity generated at a wind farm.[8] The Taxpayer Certainty and Disaster Tax Relief Act of 2020 extended the PTC for qualifying wind farm projects for an additional year, or through December 31, 2021.[9] The percentage reductions for ITCs, previously presented, also apply to PTCs for wind farm facilities that commenced construction in 2017 and thereafter.

Many states and individual taxing jurisdictions also offer incentives to wind farm developers. These incentives include state-level tax credits and property tax abatements, both of which are typically applicable only for a predetermined period of time following development of the wind farm. To help drive the development of renewable energy sources, individual states have also developed state-level RPS. In general, RPS establish the minimum amount of electricity that must be generated from renewable energy resources, including wind farms. While each state is unique, today 30 states and Washington, D.C. have an RPS in place.[10] Further, a total of eight states have adopted renewable portfolio goals, and five have adopted clean energy goals.[11]

The progress of a particular state’s RPS is tracked through the issuance of Renewable Energy Certificates (REC). A REC is generated for each megawatt hour of electricity generated from a renewable energy source. Each REC has a unique identification number that is used by an electricity generator to identify and prove that it has complied with the applicable RPS. When a generator creates more electricity from renewable energy sources than required by the RPS, thereby having excess RECs, the generator may sell the excess RECs to another generator to help meet their RPS requirements. Entities may also make use of a Power Purchase Agreement (PPA)[12] to meet the RPS requirements. A PPA is an agreement between two parties whereby an entity purchases energy derived from a power generation facility, which may include renewable energy resources like wind farms. With a PPA in place from a renewable energy resource, an entity can avoid the need to develop and maintain a large-scale renewable project and still meet certain RPS requirements. Generally, the PPA will include the rights to RECs associated with the renewable energy generated; however, in some cases a contractual agreement may be established to purchase only the RECs from the renewable energy resource.

Federal and state programs have been effective in promoting overall development, driving down cost, and advancing wind farm technologies. As of 2020, approximately 8% of the electricity generated in the U.S. came from wind, compared to less than 1% as of 1990.[13] The U.S. capacity-weighted average installed cost for a wind farm project in 2020 was $1,460/kW, a 40% decrease from the 2009–2010 timeframe.[14] In 2020, the average nameplate capacity of turbines was 2.75 MW, a 284% increase from 1998–1999. Further, compared to 1998–1999 measurements, the 2020 average rotor diameter and hub height increased 159% and 59%, respectively.[15] These technological improvements have enabled turbines to convert wind energy into electrical energy more efficiently, which has increased the average capacity factor[16] to 36% for the entire U.S. onshore wind turbine fleet.[17]

Valuation Analysis

The market value of a wind farm is determined, in accordance with USPAP, by considering each of the three traditional approaches to value: the sales comparison approach, income approach, and cost approach. The appraiser analyzes each approach to determine its applicability to the subject property being appraised, dependent on the conditions of the market in which the subject property competes, the specific nature of the subject property, and the availability of pertinent information. For purposes of this article, we will focus on the income approach to value and key issues that arise in wind farm valuations for ad valorem taxation.

Income Approach Summary

The income approach is the predominant method that buyers and sellers use to make investment decisions. This approach measures value as the present worth of the expected future cash flows that would be available to the owner of a specific income producing asset. For a wind farm, cash flows are generally forecasted based on the revenues from the sale of electricity, capacity, and RECs. Costs associated with the fixed and variable operating expenses, income taxes, future capital expenditures, and working capital changes are calculated to estimate the cash outflows. The projected future cash flows are discounted to the appraisal date using a market-based discount rate reflective of the risk perceived by a prospective investor in the subject wind farm. The sum of the discounted debt-free cash flows establishes the market value of the subject wind farm’s operating business, also known as the business enterprise value (BEV).

The BEV includes all tangible assets (property, plant, and equipment), working capital, and intangible assets of a continuing business.[18] Depending on the appraisal and the governing laws and statutes of the taxing jurisdiction, the BEV may need to be adjusted to arrive at an indicator of value for just the taxable assets. For example, if only the tangible assets of the subject wind farm are taxable and the subject of the appraisal, then any working capital and intangible asset value included in the BEV must be deducted. Federal and state incentives, RECs, PPAs, other contractual agreements, a trained and assembled workforce, permits and operating licenses, technical drawings and manuals, software, and the like are examples of intangible assets that could be associated with a wind farm and may need to be quantified and deducted from the BEV to arrive at an indicator of only the taxable assets.

Income Approach Considerations

When developing a wind farm appraisal for ad valorem tax purposes, the appraiser should be informed about the applicable statutes and laws in the subject taxing jurisdiction. Some taxing jurisdictions mandate the use of certain approaches to value and further specify the exact methodology to apply within each valuation approach. In some cases, this necessitates that the appraiser applies a jurisdictional exception in the appraisal analysis. Further, for ad valorem wind farm appraisals, the appraiser should be aware of each jurisdiction’s laws and statutes dictating what assets are taxable. Each taxing jurisdiction is different, and many have unique rules regarding the taxability of real versus personal property and tangible versus intangible assets. As a result, the appraiser must consider several key factors when developing the income approach, including income tax depreciation rules, intangible assets, tax credits, and the like.

Depreciation

When developing the income approach, the appraiser must know the applicable jurisdictional rules regarding a pre-tax versus after-tax analysis. When developing an after-tax discounted cash flow, an appraiser should be knowledgeable of the various income tax depreciation methods and IRS tax laws applicable to a wind farm.

The basis for income tax depreciation utilized in the development of the income approach is largely spelled out in the depreciation tables and schedules published annually by the IRS in IRS Publication 946 (IRS 946). As described in IRS 946, income tax depreciation can be calculated using a modified accelerated cost recovery system (MACRS) or straight-line schedules. In the case of a wind farm, a substantial amount of the property can be depreciated using a 5-year property life, meaning depreciation for that property can be calculated using a 5-year MACRS schedule when calculating the cash flow stream that is subject to income taxes.

Also, as part of the Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017, and as detailed within IRS 946, there are provisions that allow bonus depreciation to be elected for wind farms. In certain cases, a wind farm is eligible to apply 100% bonus depreciation for a certain period for qualified property. The IRS identifies the rules and criteria that must be met in order to determine whether the accelerated and bonus income tax depreciation election can be made.[19] Because of the complexity of the income tax code, an appraiser must carefully consider the appropriate income tax depreciation to recognize when developing an after-tax cash flow for a wind farm, as different income tax depreciation deductions may produce a materially different indicator of market value.

Intangible Assets

When appraising a property for ad valorem purposes, an appraiser must pay special attention to the indicator of value derived from the income approach and what assets it comprises. As previously discussed, once the present value of all the future cash flows of a property have been calculated and summed, the appraiser has developed an indicator of the BEV. As defined by the American Society of Appraisers (ASA), the BEV includes “tangible assets (property, plant, equipment, and working capital) and intangible assets of an operating business, and excludes nonoperating assets (i.e., excess land, idle equipment).”[20] However, in many taxing jurisdictions, working capital and intangible assets are not subject to ad valorem taxation.

The ASA defines an intangible asset as “an asset having no physical existence yet having value based on rights and privileges associated with it, including going concern value, goodwill, and other intangibles.”[21] As previously mentioned, examples of what might be considered intangible assets can include a trained and assembled workforce, operating permits and or operating licenses, and contractual agreements such as PPAs.[22] The ASA defines working capital as “liquid assets needed to operate the business,”[23] which is “calculated by deducting current liabilities from current assets.”[24] Working capital and some level of intangible assets are inherently captured in the BEV derived by the income approach. If they are not taxable in the applicable jurisdiction, the BEV must be adjusted to remove the value of these components. Failure on the part of the appraiser to adjust for the value of working capital and intangible assets leads to an overstated value of the taxable assets that are the subject of the appraisal. This can lead to a disconnect in the indicator of value derived from the income approach and the other approaches to value developed (cost and/or sales comparison) and thus result in a skewed conclusion of value through the reconciliation process.

Tax Credits

As previously mentioned, both federal and state incentives have been key contributing factors to the recent increase in the development of wind farms, including PTCs, ITCs, and RECs. These incentives and tax credits, particularly their tangible versus intangible nature, have become the focus of recent ad valorem tax disputes related to wind farms. As previously mentioned, in many jurisdictions, intangible assets are not subject to ad valorem taxation.

The treatment of PTCs in wind farm valuation was the focus of a recent property tax appeal in the State of Oklahoma, an example of one jurisdiction where intangible assets are not subject to ad valorem taxes.[25] On August 5, 2021, the Twenty-Sixth Judicial District Court in the State of Oklahoma ruled that PTCs should not be used in the valuation for property tax purposes.[26] In rendering its decision, the court found that the PTCs were neither tangible nor intangible property.”[27] The court also found that the right to claim the PTCs was contracted to a third party tax equity investor prior to the construction of the facility, and therefore would not be available to a willing buyer of the tangible property. While the court stopped short of opining on exactly what the PTCs represent (tangible versus intangible property), the court did determine that PTCs were not taxable for ad valorem purposes under Oklahoma law. The decision and the pending appeal have implications that appraisers should be aware of when valuing wind farms in the State of Oklahoma as well as other jurisdictions that could accept the decision as precedent for future ad valorem tax cases.

Conclusion

The cumulative amount of wind farm capacity and annual generation in the U.S. has grown substantially over the past twenty years. The growth trend for wind farms is expected to continue as less carbon-intensive sources of electricity are developed in the effort to replace traditional fossil fuel–based electricity sources. While developers and owners of wind farms were traditionally offered property tax abatements, property tax disputes have continued to rise as the abatements expire. The result has been an increase in the need for independent and unbiased appraisals of wind farms for ad valorem tax purposes. This work requires an appraiser who is current with the ever-changing energy markets, especially as they pertain to the state of the wind power generation industry. Equally important, the appraiser must be knowledgeable of the intricacies associated with the valuation of wind farms for ad valorem property tax purposes, the governing jurisdictional laws and statutes pertaining to taxable assets, and how such factors affect the appraisal analysis.

Endnotes

- “Wind Energy Final Programmatic EIS: Appendix D: Wind Energy Technology Overview,” Wind Energy Development Programmatic EIS Information Center, accessed November 3, 2021, https://windeis.anl.gov/documents/fpeis/maintext/Vol2/appendices/appendix_d/Vol2AppD_1.pdf

- “Wind Explained: History of Wind Power,” U.S. Energy Information Administration, accessed September 23, 2021, https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/wind/history-of-wind-power.php

- U.S. Department of Energy, Land-Based Wind Market Report: 2021 Edition August 2021, 3.

- “Frequently Asked Questions: What is U.S. Electricity Generation by Energy Source?”, U.S. Energy Information Administration, accessed September 23, 2021, https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=427&t=3/

- “Wind Explained: History of Wind Power,” U.S. Energy Information Administration, accessed September 23, 2021, https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/wind/history-of-wind-power.php

- Michael Rogers, “Extenders Bill – a small victory for Wind and a loss for Solar,” White & Case, December 27, 2019, https://www.whitecase.com/publications/alert/extenders-bill-small-victory-wind-and-loss-solar

- Michael Rogers and Brandon Dubov, “Stimulus Bill Brings Welcomed Changes to the Renewable Energy Industry,” White & Case, January 6, 2021, https://www.whitecase.com/publications/alert/stimulus-bill-brings-welcomed-changes-renewable-energy-industry

- Internal Revenue Service, Department of the Treasury, “Credit for Renewable Electricity Production and Refined Coal Production, and Publication of Inflation Adjustment Factor and Reference Prices for Calendar Year 2021,” Federal Register 86, no. 79 (April 27, 2021): 22300-22301, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2021-04-27/pdf/2021-08686.pdf

- Michael Rogers, “Extenders Bill – a small victory for Wind and a loss for Solar,” White & Case, December 27, 2019, https://www.whitecase.com/publications/alert/extenders-bill-small-victory-wind-and-loss-solar

- “Renewable & Clean Energy Standards,” Database of State Incentives for Renewables & Efficiency, September 2020, https://ncsolarcen-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/RPS-CES-Sept2020.pdf

- Ibid.

- A PPA is a long-term agreement to purchase a specific amount of power, capacity, or RECs at an agreed-upon price. Typical PPAs for wind farms range from 15 to 25 years, with the most common term being 20 years.

- “Frequently Asked Questions: What is U.S. Electricity Generation by Energy Source?”, U.S. Energy Information Administration, accessed September 23, 2021, https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=427&t=3/

- U.S. Department of Energy, Land-Based Wind Market Report: 2021 Edition August 2021, x.

- Ibid.: viii.

- Capacity factor is the ratio of actual net generation over a given period of time to its maximum potential net generation over that same period, represented as a percentage. If a power generation facility, like a wind farm, were to theoretically operate at full capacity for the entire year, it would realize a 100% capacity factor.

- U.S. Department of Energy, Land-Based Wind Market Report: 2021 Edition August 2021, ix.

- Machinery & Technical Specialties Committee of the American Society of Appraisers, Valuing Machinery and Equipment: The Fundamentals of Appraising Machinery and Technical Assets, 4th ed., American Society of Appraisers (Herndon, Virginia: 2020), 527.

- Internal Revenue Service: “New Rules and Limitations for depreciation and expensing under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” accessed September 23, 2021, https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/new-rules-and-limitations-for-depreciation-and-expensing-under-the-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act

- Machinery & Technical Specialties Committee of the American Society of Appraisers, Valuing Machinery and Equipment: The Fundamentals of Appraising Machinery and Technical Assets, 4th ed., American Society of Appraisers (Herndon, Virginia: 2020), 527.

- Ibid., 538.

- This list of intangible assets is not exhaustive and could include technical drawings and manuals, software, other contractual agreements, customer lists, and the like.

- Machinery & Technical Specialties Committee of the American Society of Appraisers, Valuing Machinery and Equipment: The Fundamentals of Appraising Machinery and Technical Assets, 4th ed., American Society of Appraisers (Herndon, Virginia: 2020), 119.

- Ibid., 555.

- Per Article 10, Section 6A, of the Oklahoma Constitution, intangible personal property is exempt from ad valorem taxation.

- Kingfisher Wind, LLC v Matt Wehmuller, et al. (Okla.2021)

- Ibid.

This article was previously published in the MTS Journal.